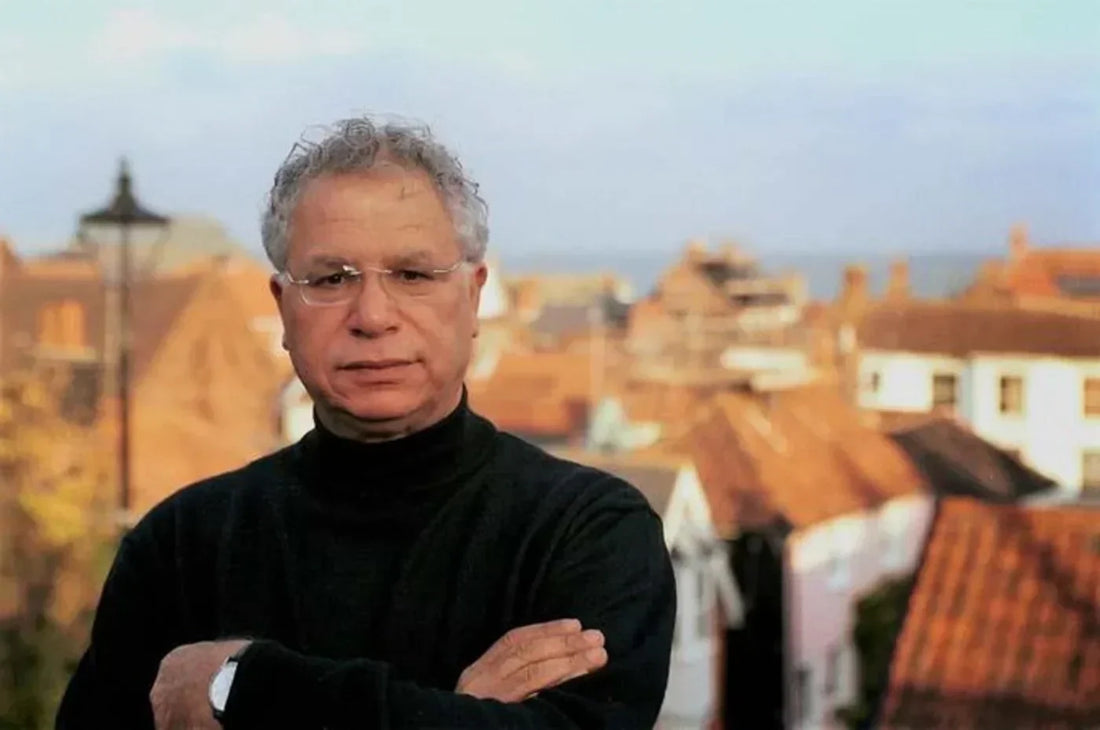

I Was Born There, I Was Born Here by Mourid Barghouti

The olive is especially important in Palestinian tradition, below is an excerpt from "I Was Born There, I Was Born Here" by Mourid Barghouti that brings the reader to understand not only how occupation wages war on the people but their connection with the land.

“I’m not familiar with these roads that Mahmoud is taking, and not just because my geographical memory has faded during the years of exile; the sad and now certain truth is that I no longer know the geography of my own land. However, the car is now traveling over open country and there’s no sign of paved roads, traffic lights, or human beings as far as the eye can see. It’s going across fields and I don’t know how this is going to get us to Jericho.

Puddles of water, stones, and wild plants, scattered through a fog that is starting gradually to lift. Everywhere you look, huge olive trees, uprooted and thrown over under the open sky like dishonored corpses. I think: these trees have been murdered, and this plain is their open collective grave. With each olive tree uprooted by the Israeli bulldozers, a family tree of Palestinian peasants falls from the wall. The olive in Palestine is not just agricultural property. It is people’s dignity, their news bulletin, the talk of their village guesthouses during evening gatherings, their central bank when profit and loss are reckoned, the star of their dining tables, the companion to every bite they eat. It’s the identity card that doesn’t need stamps or photos and whose validity doesn’t expire with the death of the owner but points to him, preserves his name, and blesses him anew with every grandchild and each season. The olive is the fruit itself (berries that may be any shade of green, any shade of black, or a shiny purplish color; that may be almond-shaped or oblong, oval or spherical) and it is recipes, processes, and tastes (semi-crushed, salted, semi-dried, scored “they’re good at. The season of their harvest, in the magical autumn, transforms the men, women, and children of the village into bards, singers, and lyric poets whose rhythms turn the tiring work into a picnic and a collective joy. The olive is the pressed oil flowing from the enormous palm-fiber pressing mats, its puzzling color somewhere between shining green and dark gold. Of the virgin oil produced from the first picking they make each other their most eloquent gifts and in the jars set in rows in the courtyards of their houses they store their peace of mind as well as the indispensable basis of their daily meals. If anyone falls ill, the oil is his medicine, and if they rub their aches with it, the pain goes away (or rather it doesn’t, but they believe it does). From its waste, they manufacture soap in the courtyards of their houses and distribute it to the groceries—Shak‘a Soap, Tuqan Soap, Nabulsi Hasan Shaheen Soap, and others. From the wood produced by the annual pruning, they carve curios, lovely wooden models of mosques and churches, and crosses. With great skill they whittle pictures of the Last Supper “the Manger, and Christ’s birth, and statuettes of the Virgin Mary. They fashion arabesque work boxes of various sizes inlaid with mother-of-pearl from the Dead Sea, along with necklaces and rosaries, horses and camel caravans, and carve them to the smoothness, luster, and amazing hardness of ivory. From the crushed olive stones they extract smooth grindings that they use as a fuel for their stoves along with or instead of charcoal, and over whose silent fire they roast chestnuts during the ‘forty days’ of the bitterest cold, leaving the coffee pot to simmer gently, quietly, over its slow heat while outside the thunder mountains collapse, gather, and then collapse again, preceded by lightning at times hesitant, at times peremptory. Next to these stoves they exchange their sly humor, make fun of their cruel situation, practice their masterful skill at friendly backbiting, and, when the visits of relatives or neighbors bring a boy and a girl together in one house, exchange flirtatious glances that combine daring with shyness. For those who don’t like coffee, they bring the blue tea pot, and sage leaves with their intoxicating perfume of the mountains.”

Excerpt From

I Was Born There, I Was Born Here

Mourid Barghouti